Kero Modular Server Engine

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Core Values

- Architecture

- Detailed Description

- Rock Paper Scissors Lizard Spock

Overview

An asynchronous, lock-free, multi-threaded, component-based modular server engine project.

Duration: April 23, 2024 ~ May 5, 2024

Github: link

Core Values

- Component-based Modular System

- Separation of functional components (hereinafter Services)

- Guaranteeing the initialization order of services based on inter-service dependencies and detecting circular references

- Inter-service communication via dependency injection and event subscription/invocation

- Actor System

- Inter-thread communication implemented using asynchronous data transfer with Lock-free SPSC queues

- Inter-service communication within a thread designed to avoid locks

- Asynchronous Structured Logging System

- Asynchronous logging implemented with thread locals and SPSC queues to prevent performance degradation due to logging

- Receives key-value pairs as arguments for various log handling

- Custom log handler extension feature

- Asynchronous IO Event Loop

- Implemented asynchronous IO communication using Linux epoll

- Implemented FlatJson and packet tokenization algorithms

Architecture

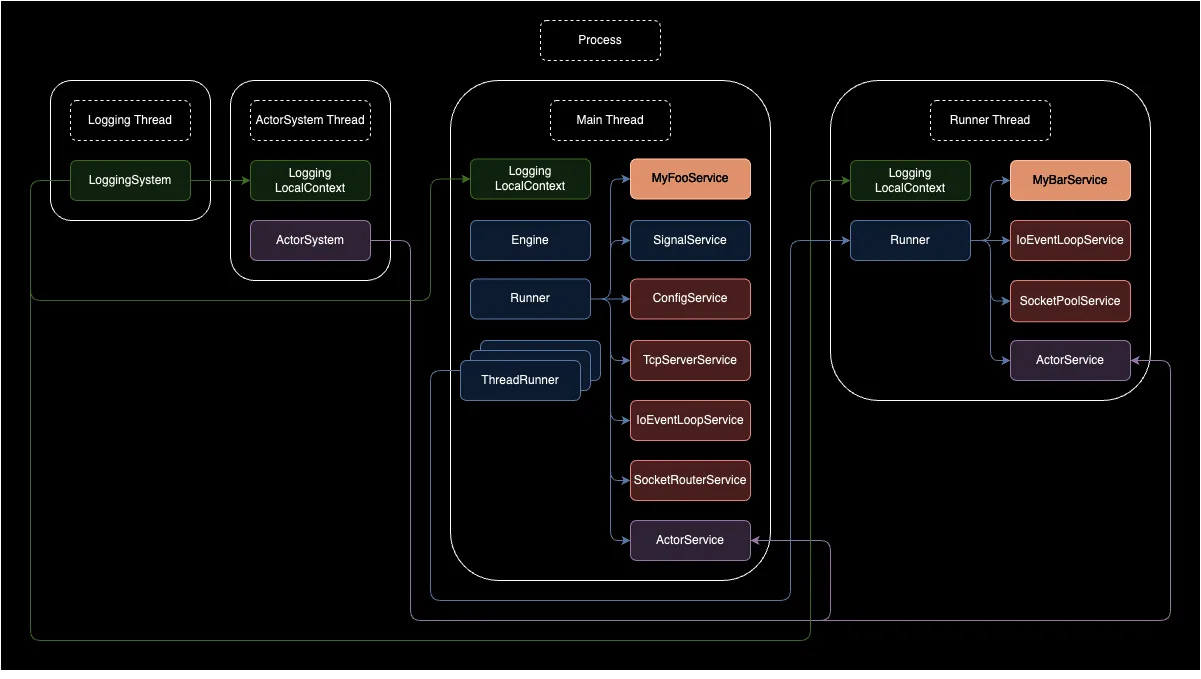

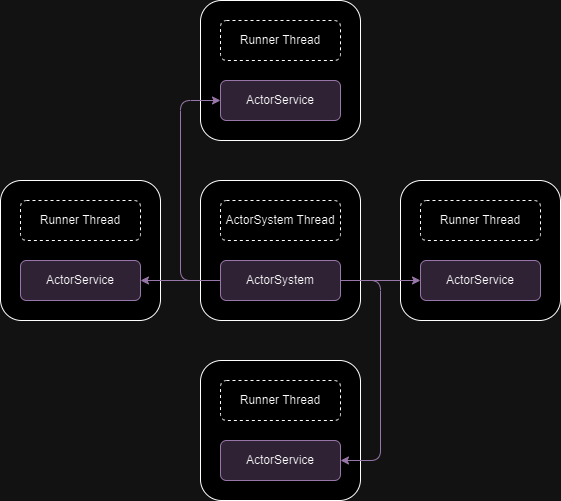

The diagram above illustrates an example of the overall architecture of the server engine. It shows which modules each thread possesses within a single server process and how these modules relate to each other.

Blue represents modules within kero/engine, and purple represents only the ActorSystem communication structure among kero/engine modules.

Red represents modules within kero/middleware that communicate with the engine only through interfaces.

Green represents modules within kero/log and expresses only the logging system communication structure.

Apricot represents user-level modules that are not included in the server engine but demonstrate that the engine can be extended by implementing services.

Detailed explanations will be provided in the detailed description below.

Detailed Description

Component-based Modular System

Most functionalities are implemented by inheriting the Service class. The Runner class owns instances of these service implementations and calls them. Below is pseudocode for the Service class.

class Service {

// Declare dependent services in the constructor

Service(dependency_declarations)

// Return reference to dependent service declaration list

GetDependencyDeclarations()

// Return reference to dependent service

GetDependency<T>()

// Called before entering the update loop, according to the dependency structure

OnCreate()

// Called every time in the update loop

OnUpdate()

// Called after exiting the update loop

OnDestroy()

// Event subscription and invocation methods

SubscribeEvent(event)

UnsubscribeEvent(event)

InvokeEvent(event, data)

}Guaranteed Initialization Order of Dependent Services

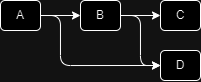

In the service’s constructor, ServiceKindIds of dependent services are stored as a list. When the Run function of the Runner (hereinafter Runner) class is called, it traverses the dependency service graph by calling the GetDependencyDeclarations() method of the services it owns. The diagram below shows an example of inter-service dependency structure.

- A depends on B and D.

- B depends on C and D.

A class called ServiceTraverser traverses such services using a depth-first search from the beginning. Below shows the traversal process for the above dependency structure:

Visit A and mark A as visited.

Among A's dependencies B, D, visit B and mark B as visited.

Among B's dependencies C, D, visit C and mark C as visited.

Since C has no dependent services, call C's `OnCreate()` and return.

Visit D, B's dependency, and mark D as visited.

Since D has no dependent services, call D's `OnCreate()` and return.

Since all of B's dependent services have been visited, call B's `OnCreate()` and return.

Since D has been visited for A, do not visit D again.

Since all of A's dependent services have been visited, call A's `OnCreate()` and return.As a result, initialization proceeds in the order of C → D → B → A.

The reason for including the dependent service graph traversal function was to ensure the initialization of dependent services, as the initialization logic for services occurs in OnCreate().

For example, ConfigService parses CLI arguments and owns data in OnCreate(). Other services depending on ConfigService needed its initialization to be guaranteed.

Additionally, putting the dependency list in the constructor provides an extra benefit: it ensures the existence of that service during runtime logic processing. If there were no dependent service list, one would have to implement methods like FindService() and only check for existence during logic processing. To some extent, this makes complex service structures difficult to change and often creates room for crashes in live services that are not frequently handled.

To draw an analogy with programming languages, a compile-based language throws an error at build time if a class method is deleted, whereas a script-based language throws an error at call time if a class method is deleted.

Service Dependency Injection

After initializing dependent services as above, the actual ownership of the service instances resides with the Runner, and references are stored so that the service can access dependent services. The service can access and call dependent services through the GetDependency<T>() method.

This is similar to dependency injection features in Java/Kotlin Spring Framework and Node.js based Nest.js.

As a result, the Runner delegates the creation and access of dependent services, allowing the service to focus on implementing its logic.

Circular Reference Validation of Dependent Services

While the guaranteed initialization order of dependent services feature solved this problem, traversing the dependency service graph can lead to infinite recursion if a circular reference occurs. The diagram below shows an example of a circular reference.

- A depends on B.

- B depends on C.

- C depends on A.

In such a structure, the order of circular reference occurrences should be provided to the user, and an error should be raised.

Below is the circular reference validation process when traversing services as above:

Visit A.

Check if A is in the visit stack.

Since A is not in the visit stack, add A.

Visit B, A's dependency.

Check if B is in the visit stack.

Since B is not in the visit stack, add B.

Visit C, B's dependency.

Check if C is in the visit stack.

Since C is not in the visit stack, add C.

Visit A, C's dependency.

Check if A is in the visit stack.

Since A is in the visit stack, print everything after this stack depth and return an error.As a result, A → B → C → A is printed, and an error is returned.

In such cases, the user must resolve this circular reference between services. Two recommended methods exist.

First, split some of the functionality of the service where the cycle occurred. The diagram below shows an example of a solution using service splitting.

- A depends on B.

- B depends on C.

- C depends on D.

- A depends on D.

By separating some of A’s functionality into the D service and making A and C depend on D, the circular reference can be resolved. The second method will be explained in the next chapter.

Event Subscription and Invocation

Event subscription and invocation are ways to pass data between services via callbacks. At this time, since the services are owned by the Runner, they do not leave the Runner’s scope. And the Runner does not leave the thread’s scope. Therefore, event invocation is thread-safe.

Regarding the circular reference resolution method for the circular reference validation feature of dependent services, I will explain the second one.

Secondly, you can use event subscription and invocation without depending on services at all. This is an asynchronous approach to writing and processing logic. Below is an example of pseudocode for implementation:

class A : Service {

OnCreate() { SubscribeEvent("request_foo") }

OnEvent(event, data) {

if (event == "request_foo") {

// After processing data for request_foo, call the result event invocation

InvokeEvent("response_foo", response_data)

}

}

}

class C: Service {

OnCreate() { SubscribeEvent("response_foo") }

OnEvent(event, data) {

if (event == "response_foo") {

// Process data for response_foo

}

}

}When the SubscribeEvent() method is called in a service implementation, the OnEvent() method is called when the InvokeEvent() method is called.

At this time, events are called synchronously. In other words, the call stack of that event call does not disappear. Therefore, the state can be stored in the service’s member variables. Below is an example of the call stack’s pseudocode from the event invocation in Service C:

C.foo_state = "bar"

C.InvokeEvent("request_foo", request_data)

A.OnEvent("request_foo", request_data)

A.InvokeEvent("response_foo", response_data)

C.OnEvent("response_foo", response_data)

assert(C.foo_state == "bar")The example above shows how a dependent service’s method call can be changed to an event invocation. However, for a 1:1 request-response call structure, writing logic synchronously is more intuitive and the call structure is simpler, so it is more recommended.

Events are useful in a 1:N event processing call structure. For example, suppose a user purchases a paid item, and payment processing and a purchase notification to the company Slack are assumed. At this time, it is also assumed that payment processing and sending purchase notifications are IO-intensive tasks. If payment processing is done after sending a purchase notification, the user may experience payment delays during the time it takes to send the purchase notification. If payment processing and sending purchase notifications can proceed in parallel, the user will not experience payment delays.

Since InvokeEvent() calls handlers sequentially and thread-safely within a thread, a method for parallel event processing is needed.

In the next chapter, I will explain what an Actor System is, why it is needed, how it was implemented, and how it is used.

Actor System

One of the most commonly used methods for exchanging data between threads is to use shared resources and locks on those resources. However, as the number of shared resources increases, the waiting time to acquire locks also increases, which means that multi-threaded resources are not utilized properly.

The Actor System is one of the inter-thread communication methods. The advantage of the Actor System is that data can be exchanged between threads without shared resources. Since there are no shared resources, threads do not wait. This means that multi-threaded resources can be utilized properly.

Structure and Operating Principle

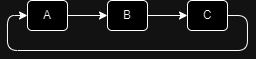

The diagram above shows the relational structure between the Actor System and ActorService (hereinafter Actor Service). It consists of an Actor System thread and Runner threads. The Actor Service within the Runner thread was implemented as a Runner’s service. The Actor System and Actor Service have a 1:N relationship.

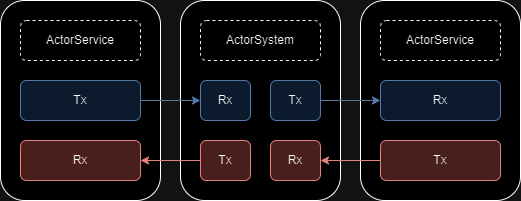

The diagram above illustrates the implementation using SPSC queues between the Actor Service and the Actor System. Tx -> Rx represents one SPSC queue. Communication between Actor Services occurs through SPSC queues mediated by the Actor System.

Each Actor Service has a unique name. The SendMail(to, event, data) method of the Actor Service is an asynchronous call. The SPSC queue is a Lock-free implementation without shared resources and locks. When this method is called, it pushes to the SPSC queue and returns immediately. In the loop within the Actor System thread, if there is data in Rx, it pops it and pushes it to the Tx of the Actor Service corresponding to to. The OnUpdate() of the Actor Service is called in the Runner’s update loop, and if there is data in Rx, it pops it and calls InvokeEvent(event, data).

By implementing the Actor System, events can be delivered between multiple Runners, i.e., multiple threads, without shared resources and locks. And by calling the BroadcastMail(event, data) method, events can also be delivered to all Runners except the current one.

Examples of utilizing the Actor System

For example, Redis (hereinafter Redis) in-memory DB processes all queries sequentially, one at a time. If a Redis client uses a synchronous method, that thread will be blocked and unable to process other logic until the function returns. Let’s create a separate Redis Runner thread that owns the Redis client service. If the logic Runner thread processes logic and sends Redis query events to the Redis Runner thread, the logic Runner thread will not be blocked and can process other logic. After the Redis Runner thread processes the Redis query event, if it sends a Redis result event to the logic Runner thread, the logic Runner thread can process many other logics before processing the Redis result event.

As such, using the Actor System allows for efficient use of multiple threads without locks and waiting.

Asynchronous Structured Logging System

Logging is a very important function in applications. Many problems are solved by narrowing down the scope of the problem and obtaining clues based on logs. Therefore, many logs that help solve problems should be written in appropriate places.

However, logging is an IO-intensive task. When writing logs to stdout/stderr during logic processing, calling logging web APIs, or adding logs to a log DB, logic processing is likely to be delayed. Although logging is essential for problem solving, it is regrettable that it affects performance because it is not directly related to immediate logic processing.

Therefore, I devised a method that can process logging asynchronously and non-blockingly. It utilizes a logging thread and thread local.

Structure

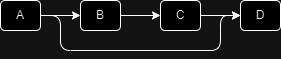

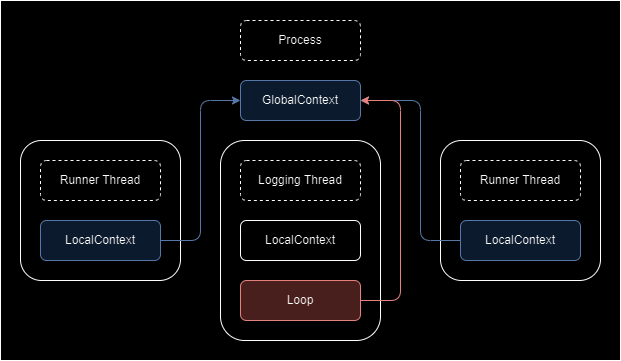

The diagram above shows the structure of the logging system. LocalContext (hereinafter Local Context) is the Tx of the SPSC queue in thread local. GlobalContext (hereinafter Global Context) is the set of Rxs of the SPSC queue.

Implementation Explanation

log::Debug("user created").Data("user_id", user_id).Log();

log::Error("invalud user id").Data("user_id", user_id).Log();The code above is an example of a log call, and I will explain the implementation based on this example.

When calling log::Debug(message, location = current()) log::Info(message, location = current()) log::Warn(message, location = current()) log::Error(message, location = current()) functions, an instance of the LogBuilder (hereinafter Log Builder) class is created with the message, code file name, file line, file column, and function name as arguments. The pseudocode for the Log Builder class is as follows:

namespace log {

class LogBuilder {

// Receives log level, message, and code location as arguments

LogBuilder(level, message, location) {}

// value is a generic type T and must have a specialization for operator<<

[[nodiscard]]

Data<T>(key, value)

// Push log to LocalContext in thread local

Log()

}

Debug(message, location = current()) { return LogBuilder{kDebug, message, location} }

Info(message, location = current()) { return LogBuilder{kInfo, message, location} }

Warn(message, location = current()) { return LogBuilder{kWarn, message, location} }

Error(message, location = current()) { return LogBuilder{kError, message, location} }

} // namespace logAn instance of Log Builder is created, and key-value pairs are added via the Data() method. When the Log() method is called, it pushes to the Local Context Tx and returns immediately. This is non-blocking logging without IO operations during logic processing. Of course, the processing is not yet complete.

Log Processing Function

The logging thread pops data from the Rxs in the Global Context and calls the OnLog(log) method of the stored Transport (hereinafter Transport) implementation.

Transport is responsible for receiving and processing log data. It has a default ConsolePlainTextTransport implementation and was interfaced so that users can implement new log data processing without modifying the server engine source code. Multiple transports can also be added.

Log Loss Problem and Solution at Runner Thread Termination

The Local Context instance resides in thread local, and the Local Context’s lifecycle is aligned with the thread local’s lifecycle. When the Log() method of Log Builder is called, the GetLocalContext() global function is called, and within this global function, the thread local instance and a once flag are used to initialize it only when called. The reason for initializing only when called is that there is no need to create an SPSC queue’s Rx in the Global Context for threads that do not perform logging.

The problem was that logs were lost when threads terminated. This was because there is a part in the Local Context destructor that deletes the SPSC queue’s Rx from the Global Context. However, the logic for deleting from the Global Context is necessary to prevent Rx leakage when threads terminate. Therefore, before deleting from the Global Context, all logs were popped from the Rx and pushed back to orphaned_logs (hereinafter orphaned logs), and then the Rx was deleted. And the logging thread was made to process orphaned logs first.

Log Loss Problem and Solution at Main Function Termination

The actual logging occurs not when the log function is called but when it is processed within the logging thread. I tried to implement the server to shut down when it receives a SIGINT signal, and I made it send a termination message to the logging thread and exit the loop within the logging thread when it receives a termination event.

However, since the logging thread exited the loop without processing all logs, logs were lost. So, when sending a termination message to the logging thread, I also sent a processing threshold time, and the logging thread was made to exit the loop if it reached the processing threshold time or if there were no logs after receiving the termination message. And the processing threshold time could be received as an argument.

Asynchronous IO Event Loop

I worked on the project in a Linux environment. I used Windows Subsystem for Linux on Windows PCs and Docker containers on macOS. Therefore, I used epoll, an asynchronous IO system similar to Windows’ IOCP and macOS’s kqueue. I chose an asynchronous IO system because, as explained in the chapters above, implementing it synchronously/blockingly would prevent processing multiple logics and waste thread resources.

Implementation using Event Subscription and Invocation System

TcpServerService creates the server’s file descriptor (hereinafter fd), registers it with IoEventLoopService, and subscribes to the socket_read event. If the socket_read event and data socket_id were the server’s fd, it created a client fd, assigned the client fd to the socket_open event and data socket_id, and invoked the event.

When the client disconnected, the return value of recv() was 0, in which case it invoked the socket_close event and data socket_id.

The SocketPoolService class is a service that embodies the concept of owning sockets. Since business logic is implemented by inheriting this service, handling events with string matching in OnEvent() can lead to long if or switch statements. Therefore, I implemented RegisterMethodEventHandler(method) to register a method, so that when the corresponding event occurs, that method is called.

When Multi-Platform Implementation is Needed

I implemented the IoEventLoopService class by referring to Linux epoll non-blocking examples. If Windows’ IOCP or macOS’s kqueue needs to be used, I would likely abstract the IoEventLoopService implementation one step further using the pimpl pattern.

Packet Reading After Multiple Packet Writes

While implementing the server engine, I also developed a simple game to verify its functionality.

Since it was during feature implementation, I chose to use a readable string-based approach rather than binary serialization/deserialization for server-client communication data to easily check for errors when they occurred.

For string serialization/deserialization, I considered csv-based key=value pairs or JSON. Since csv required additional features to separate packet string blocks, I decided to use JSON. This is because JSON objects can be delimited by { and } for their start and end.

Since this project was implemented from scratch, I tried to implement JSON. However, implementing all JSON specifications might be over-engineering for the current project, so I only implemented the necessary functionalities. Below are the implemented specifications:

- A JSON string can only start with a JSON object.

- JSON value types can only be boolean, number, or string.

I named it FlatJson and implemented FlatJsonParser for deserialization and FlatJsonStringifier for serialization.

Having recently implemented a compiler, I implemented FlatJsonParser as an LL(1) recursive descent parser.

{"key":"value"}{"key2":"value2"}In cases like the example above, where there are multiple packets in the buffer, I implemented FlatJsonScanner (hereinafter Scanner) to tokenize them into JSON object units. It reads from the buffer, concatenates strings via the scanner’s Pop(buffer) method, and tokenizes and returns the string when the Pop() method is called.

FlatJson Tokenization Implementation

During tokenization implementation, the parenthesis-matching algorithm came to mind. This is because, according to FlatJson syntax, tokenization had to be done based on the current parentheses.

And since only { and } parentheses were needed, instead of a stack, a single integer variable was incremented (++) and decremented (--) to match the parentheses.

And since packets might not have correct parenthesis pairs due to various logics and systems, I decided to discard incorrect ones and start anew. The only correct case is starting with a { parenthesis, and since newly allocating string objects every time can be a memory waste, I applied the sliding window algorithm. When a { parenthesis is encountered, the start index is moved to the parenthesis, and when a } parenthesis is found, it is tokenized.

By applying the parenthesis-matching and sliding window algorithms, I was able to implement it with O(n) complexity.

Rock Paper Scissors Lizard Spock

Github: link

A console text input-based 1:1 matching multiplayer game project that was developed alongside the Kero Modular Server Engine.

Duration: April 23, 2024 ~ May 5, 2024

Core Values

- Implementation of Rock Paper Scissors Lizard Spock (hereinafter rpsls) gameplay

- Simple 1:1 matching system and load balancing system

- Example project for implementing a server engine

RPSLS Gameplay Implementation

RPSLS Game Rules

RPSLS is an extended version of Rock Paper Scissors introduced in The Big Bang Theory.

If Rock, Paper, and Scissors are defined as actions, rpsls has 5 actions.

The following is a snippet of comments from the code that explains the rules of the rpsls game well.

- rock -> lizard -> spock -> scissors -> paper -> rock

- each defeats next(1) and next(3) in the sequenceEach action beats the action in the next space and the action in the space after that.

- Rock beats Lizard and Scissors.

- Lizard beats Spock and Paper.

- Spock beats Scissors and Rock.

- Scissors beats Paper and Lizard.

- Paper beats Rock and Spock.

And the same actions result in a tie.

Gameplay Implementation

Upon connecting, players wait in the lobby and receive and display their socket_id from the server.

[DEBUG] Server: {"socket_id":9,"event":"connect"} (33bytes)

Connected to the server with socket_id: 9If there are two or more players in the lobby thread, they move to the battle thread with the fewest players among the battle threads.

After moving to the battle thread, the two players receive the opponent’s socket_id from the server, print a game start message and the opponent’s socket_id, and then prompt for action input.

[DEBUG] Server: {"opponent_socket_id":8,"battle_id":1,"event":"battle_start"} (61bytes)

Battle started with battle id: 1 and opponent socket id: 8

Please enter your action: Available actions: rock, paper, scissors, lizard, spockThe player types a possible action and presses Enter.

spock

Move sent to the server. Waiting for the opponent's action.Once both players’ actions are sent to the server, the server processes them, and the battle result is printed to the client.

[DEBUG] Server: {"result":2,"event":"battle_result"} (36bytes)

Battle result: lose

You lost the battle.Implementation Details

When a player connects to the server, the socket (player) is registered within the lobby thread.

Simple 1:1 Matching System

If there are two or more sockets, they are unregistered to be moved to another thread.

Load Balancing System

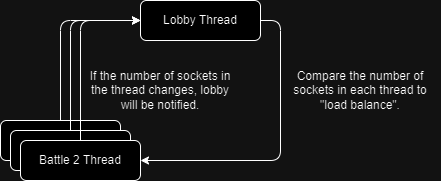

Then, the two sockets are passed to the battle thread with the fewest sockets, and a battle_start event is also sent. The diagram below illustrates the event flow between the battle thread and the lobby thread.

The battle thread registers the sockets and sends the battle_start event to the players.

In terms of gameplay, when a player’s action is sent, it is saved.

And if both players have sent their actions, the server immediately calculates the result.

Then, the result is sent to the players.

Example Project for Server Engine Implementation

While implementing the server engine, some aspects that were not initially considered were discovered and implemented as engine features through this example project.

- Communication data serialization/deserialization

- Communication packet tokenization

- Instance method-based event handling

It seems that implementing various game types will help further identify necessary features for the server engine.

If binary serialization/deserialization like Protocol Buffers were added, it might be possible to implement typed Stub functions to be generated and called. Since it’s asynchronous, it would be necessary to develop a tool to monitor the throughput of Push and Pop operations in the queue.